Scientists think one of Uranus’ moons may once have had an ocean roughly 100 miles deep — about 40 times deeper than the Pacific Ocean — and could still possibly hold remnants of it.

New computer simulations suggest Ariel, Uranus‘ fourth-largest moon, might have developed an ocean when its orbit was more stretched like an oval in space. If that had happened, Uranus’ gravity would have produced tidal forces strong enough to generate internal heat in Ariel, melting part of its icy crust.

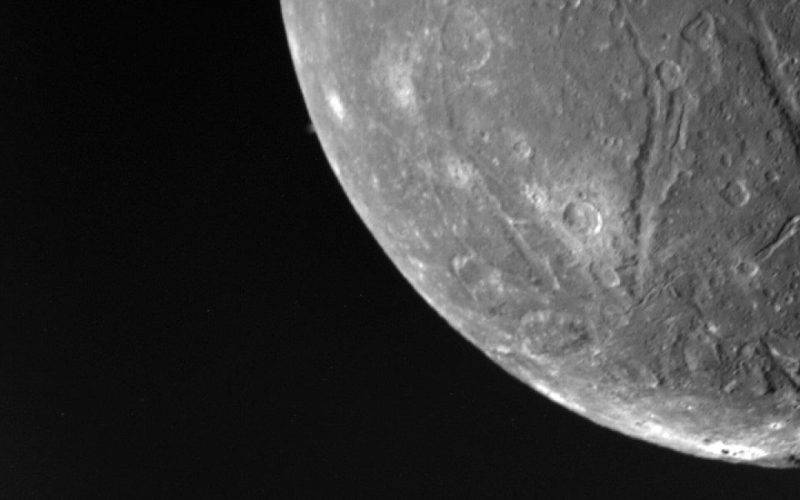

That stress could explain mysterious cracks and other surface deformities that can be observed on the moon today, said Caleb Strom, first author of the research that appeared in the journal Icarus. Those features — wide canyons, long fractures, and smooth refrozen plains — were first seen in NASA‘s Voyager 2 spacecraft images in 1986.

“It is less that the ocean is causing the cracks than that the ocean is a result of the tidal heating that would also create a thin ice shell, subject to flexing,” Strom told Mashable. “Thus, you would logically get both a subsurface ocean and a thin ice shell since part of the ice shell would have to melt.”

If the findings bear out, Ariel could be part of a growing list of icy moons in the outer solar system thought to harbor liquid water under their crusts. Similar to Saturn’s Enceladus or Jupiter’s Europa, Ariel could once have had the conditions for chemistry that can start life. Understanding how it heated, cooled, and resurfaced may help scientists learn how habitable environments can exist far from the sun.

Uranus, a planet 1.8 billion miles from Earth, has recently garnered attention for a newly discovered moon, bringing its count up to 29. For decades, the icy world was thought of as merely a bright, featureless ball.

Recent studies and new observations by the James Webb Space Telescope have changed that image, revealing it as a much more intriguing place, made of water, methane, and ammonia, wrapped around a small rocky core. Its system of moons is also part of that mysterious complexity. The new study on Ariel follows a paper last year by the same team with similar findings on Miranda, another Uranian moon.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / PSI / Mikayla Kelley / Peter Buhler illustration

“We are finding evidence that the Uranus system may harbor twin ocean worlds,” said Tom Nordheim, a co-author from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, in a statement. “Ultimately, we just need to go back to the Uranus system and see for ourselves.”

The researchers believe the tidal effects responsible for creating an ocean within Ariel likely happened 1 to 2 billion years ago as the moon’s orbit was caught in a gravitational rhythm with another Uranian moon.

Scientists call these synchronized orbits “resonance,” a rhythm that can be broken easily over time. When Ariel’s resonance ended, the moon could have cooled off, its orbit could have become more circular, and the hypothetical ocean might have started to refreeze, according to the paper.

Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / Joseph DePasquale

Spectroscopic detections point to ammonia and carbon compounds on Ariel’s surface. Because these chemicals break down quickly in space, finding them means they probably surfaced from the moon’s interior relatively recently. This supports the idea that Ariel’s surface and interior have continued to interact, potentially through past or ongoing cryovolcanism, a process in which water or ammonia erupts like lava from underground reservoirs before freezing solid.

The cracks on Ariel’s surface could have formed in ways other than tidal forces, Strom said. The ice shell could have thickened as water inside froze and expanded, causing fractures, or those hypothetical ice volcanoes could be the source. But those explanations are less certain, he said.

“Cryovolcanism is a lot more controversial since we don’t really know how cryovolcanism works,” Strom said, “and some planetary scientists are skeptical that it happens at all.”